Olive Morris: Forgotten activist hero By Lizzie Cocker

29 October, 2009 — The Morning Star Online

Reproduced in its entirety with permission of the author.

Introducing an inspirational civil rights campaigner whose life and work offer important lessons for the left.

In an age when xenophobia and Islamophobia are being stoked by illegal wars and immigration myths, the need to wrench hidden realities from history in order to see today’s truths has never been more urgent.

And thanks to the Remembering Olive Collective (ROC) founded in 2008, a bit of this history became available to the public last week at the Lambeth Archives in Brixton, south London.

Olive Morris, despite her awe-inspiring short life, remains virtually unknown. And she is one of the greatest unsung heroes I have ever come across.

My encounter with Morris began when a friend switched on my radar for forgotten female protagonists. He mentioned a local project he was doing on four practically unheard-of women activists who left in their wake cultural, social and political improvements which are enjoyed not just in London but in some instances internationally.

Three of these women were black.

With my radar on standby, I stumbled across a website which asked me if I “remember Olive Morris?” above a picture of a young black woman smiling with her shades on behind a megaphone.

No, I thought. I had never heard of Olive Morris.

And as I investigated further it became apparent that my ignorance was widespread.

Morris died aged just 27 in the 1970s. But she had such an unshakeable impact on those who knew her that many of the people with memories, documents, photographs and letters relating to this young woman responded to ROC’s calls to make her story a matter of public record.

As a tireless campaigner for black women, a socialist and an internationalist, Morris dedicated herself to fighting injustice wherever she saw it.

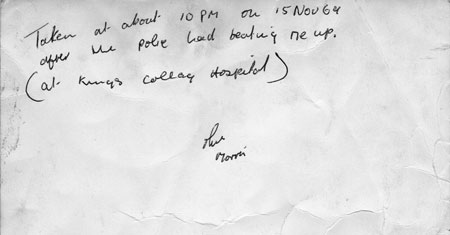

One of the most vivid examples was in 1969 when police arrested a Nigerian diplomat in Brixton as he stepped out of his Mercedes.

The police were so stunned to see a black man with such a flashy car that their reflex was to treat him as a criminal who had stolen it.

Crowds gathered round gaping as the police began to beat him.

A 17-year-old Olive struggled through the spectators and physically tried to stop the attack.

She was flung down and subjected to black police boots kicking her in her breasts. She was stripped naked and told as the blows kept on coming: “This is the right colour for your body.”

One Nigerian student wrote in tribute to her upon her death: “It is reasonable to expect that Olive Morris’s heroism will be immortalised alongside such black luminaries like Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X and many others who were proud to be black.”

But despite this ROC found while putting the jigsaw of her life story together that this woman remained only in the memories of those whose lives had crossed hers.

So vivid were the memories that these pieces of the jigsaw have now found an eternal home in the archives.

As I hungrily sifted through them trying to complete my own puzzle, it was Morris’s typewritten words that climbed out of the papers desperate to deliver the answers for problems we continue to face today.

A graduate in social sciences from Manchester University, Morris wrote numerous essays on Marxism, race and class. As a Brixton Black Panther, part and parcel of her membership was to attend lessons in Leninism and Marxism.

This education and her own activism influenced her relationship with progressive movements and she ultimately became frustrated with the British left, which she described as having “more in common with the ruling class and royalty than with fellow workers.

“Today increasingly the British working class is faced with a choice either to defend the ‘national interest’ or throw their lot in with the oppressed people of the Third World.

“The most immediate way in which this can be done is for them to support the struggle of the Third World people in this country,” she argued.

Morris sympathised with Trinidadian activist Claudia Jones who was poorly treated by the Communist Party, which failed to acknowledge her far-reaching capabilities and consigned her to an administrative role, and Grunwick striker Jayaben Desai who was virtually abandoned by trade unions.

She became disillusioned by institutions for the working class, which instinctively she would have had the most natural allegiance with.

“We have used the great British tradition of trade unionism to try and further our cause for equality and justice, but on countless occasions we have found that the movement does one thing for white workers and another for black workers,” said Morris.

“White workers have time and time again refused to give our unions recognition, they have crossed our picket lines for racist reasons, they have organised against our organisation in the trade unions.

“Take for instance STC (Standard Telephones and Cables Ltd) where white trade unionists and union officials – with exception of a few – put skin colour before the overall interest of the proletariat and often resorted to physical violence against their black fellow workers.”

Morris was exasperated by what she saw as an inherent self-interest that blocked mainly white apparently progressive groups from seeing where the real battles needed to be fought. She lambasted the Anti Nazi League “trendies” for busying themselves with “shouting their empty phrase of ‘black and white unite and fight’.”

Empty, she said, “because there was no sound basis on which such unity could be built.”

The ANL, she continued, has “become one big carnival jamboree of political confusion for the middle class.

“It doesn’t raise the political questions. It buries them in the name of ‘broadness’.”

Morris highlighted that the National Front, which the ANL directed all its enthusiasm into fighting, was merely a symptom and not a cause of the racist ideologies and practices which prevailed in every sector of society.

As the black groups Morris worked with organised to fight oppression on all levels – running supplementary schools, clubs and recreational facilities, clubbing together to buy houses, striking, organising pickets and circulating petitions – she urged people truly dedicated to fighting racism to confront the issues which affect black people’s lives on a daily basis in schools, the police, local government and even trade unions.

“Not a single problem associated with racialism, unemployment, police violence and homelessness can be settled by ‘rocking’ against the fascists, the police or the army,” she said.

“The fight against racism and fascism is completely bound up with the fight to overthrow capitalism, the system that breeds both.”

The symptomatic BNP and other far-right organisations are rearing their ugly heads above the fertile ground laid by a political framework which has perpetuated the criminalisation, social immobility and isolation of black and ethnic minorities.

But black history has a lesson for the left.

As long as support is only forthcoming when racism is so visible that it can no longer be ignored rather than being part of the daily battles against all discrimination that permeates society, the struggle to create equal conditions for everyone will keep taking one step forward and 10 steps back.

To get a glimpse into the rest of Olive’s life visit rememberolivemorris.wordpress.com or visit the collection at the Lambeth Archives in the Minet Library, 52 Knatchbull Road, London SE5 9QY.

Olive Elaine Morris

Born in 1952 in Jamaica and moved with her family to Britain aged nine

Died of cancer in 1979

Travelled to China, north Africa, Ireland and Spain

A council building in Lambeth bears her name

Groups she cofounded or worked with:

The Black Panther Movement (later the Black Workers Group),

Brixton Black Women’s Group

The Organisation of Women of Asian and African Descent

Manchester Black Womens Co-operative

National Co-ordinating Committee of Overseas Students

Black Womens Mutual Aid Group

Brixton Law Centre

The squatter movement

Comments